“I’m so short I can’t reach the door handle.” . . . “I’m so short I could walk out under that closed door.” “I’m so short . . . .”

I had heard statements like these from my predecessor as Intelligence Officer at Commander Naval Special Warfare Group, Pacific in early 1971 as he approached the conclusion of his active duty. Being “short” meant that your time to leave active duty was drawing near, you were a “short-timer.”

Around this time 50 years ago, I was very short. I believe I only had this weekend — July 17-18 — to go before my final day in Coronado (at least until 1982).

It wasn’t originally supposed to happen that way. I believe I would have normally been due to be on active duty until February 1972, three years after receiving my commission as an officer in Newport, R.I. As mentioned before, however, U.S. involvement in Vietnam was winding down. Troops were being withdrawn and the various services were looking to reduce the number of active duty members, and the expense they represented.

The Navy had announced, probably in the spring, an early-out program for officers. One had to request it and have that request approved by his or her command. I very much wanted to end my active duty early so that I could join the Class of 1972 at Columbia’s School of Journalism. I had been accepted into the Class of 1969 while a senior at Boston College, but had to postpone attending because of pending Navy duty. Columbia had offered me admission to a later class once I was able.

Would I be able to enroll in September, though? I held a billet.

I had mentioned that I had begun to work closely with CDR Robinson, the Chief Staff Officer. As had the XO on USS Biddle (DLG-34) back in 1969, CDR Robinson thought I could present ideas in writing fairly well and I was assigned to draft various administrative reports. He asked that I look at future staffing levels in anticipation of a lower level of activity involving Vietnam, indeed expecting no activity soon.

The Intel shop at COMNAVSPECWARGRUPAC had billets for two officers — the Intelligence Officer and Assistant Intelligence Officer. I had moved up to Intelligence Officer with the departure of LT Webber, and there was a LTJG ordered to the command to be my assistant.

In the draft staff organization I submitted to CDR Robinson, there was a billet for only one Intelligence Officer. The reduced scale of operations did not require two officers, especially since the Assistant had previously deployed with SEALs in-country.

Concurrent to this study, I also had contacted Columbia requesting confirmation that I would be permitted to enroll that September if I was no longer on active duty. Columbia sent me a letter with that confirmation.

Armed with the letter from Columbia, I met with CDR Robinson. Pointing out that my proposal for staffing of the Intel shop called for one officer and that a second officer was due to report shortly, I submitted my request for an early release from active duty along with the letter from Columbia. It may be purely conjecture, but my memory is that CDR Robinson, after looking over the forms I had submitted, gave me a look that said, “You got me.”

He recommended my request be approved by the CO and it was. I was going to get out early!

There was a luncheon for me at some point, with bon mots and digs from several colleagues. I don’t remember much from this brief event and Fred Palmore, one of my closest colleagues, remembers it not at all.

I still have the plaque I was given, however, and it is pictured here.

The last line reads,” Outstanding as usual. Yawn.” I think CDR Robinson was a little puzzled by that when he read it as he presented it to me. He was the senior officer who most often attended my weekly intelligence briefings to the staff. It was not uncommon for him to nod off briefly during my scintillating presentations. When I concluded the briefing, the lack of my sonorous voice would occasionally startle him awake. Sometimes failing to stifle a yawn, he would say, “Thanks, Bill, Outstanding as usual.”

I don’t remember doing anything special on that last weekend. I certainly expect I spent some time with Fred and his wife, Pam, and with Randy Middleton and Rusty Russell, other JGs on the staff.

I do remember, however, earlier getting a release-from-active-duty physical at the Navy hospital in San Diego. After reviewing my chest x-ray, the doctor told me there was a spot on one of my lungs. After reviewing my chart, which described the low-level “crud” I had experienced in late summer 1970, he figured the spot was from a bout with San Joaquin Valley Fever. (At Columbia, I had another chest x-ray, in which they found no spot.)

I also remember having to check out from various departments at the command. At the supply department, located “on the beach” near where SEALs and UDT trained, the petty-officer-in-charge asked where I was heading. Told him I would be attending graduate school in New York City. I remember him remarking about how cold it got there, and then issuing me a camouflage heavy jacket with liner. This may well be admitting to a violation of something, but I still have that jacket 50 years later (maybe there is a statute of limitations). It kept me warm many days in New York and later.

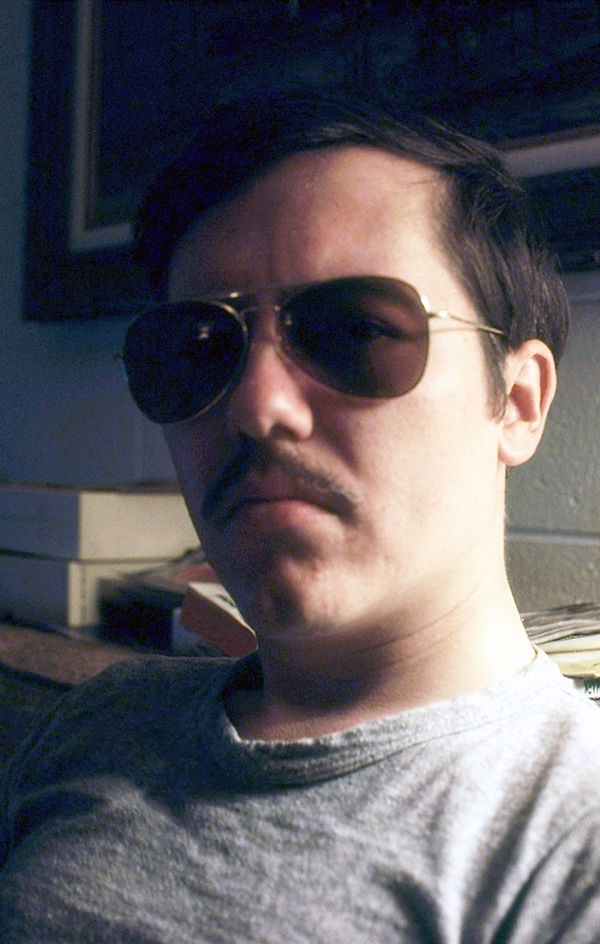

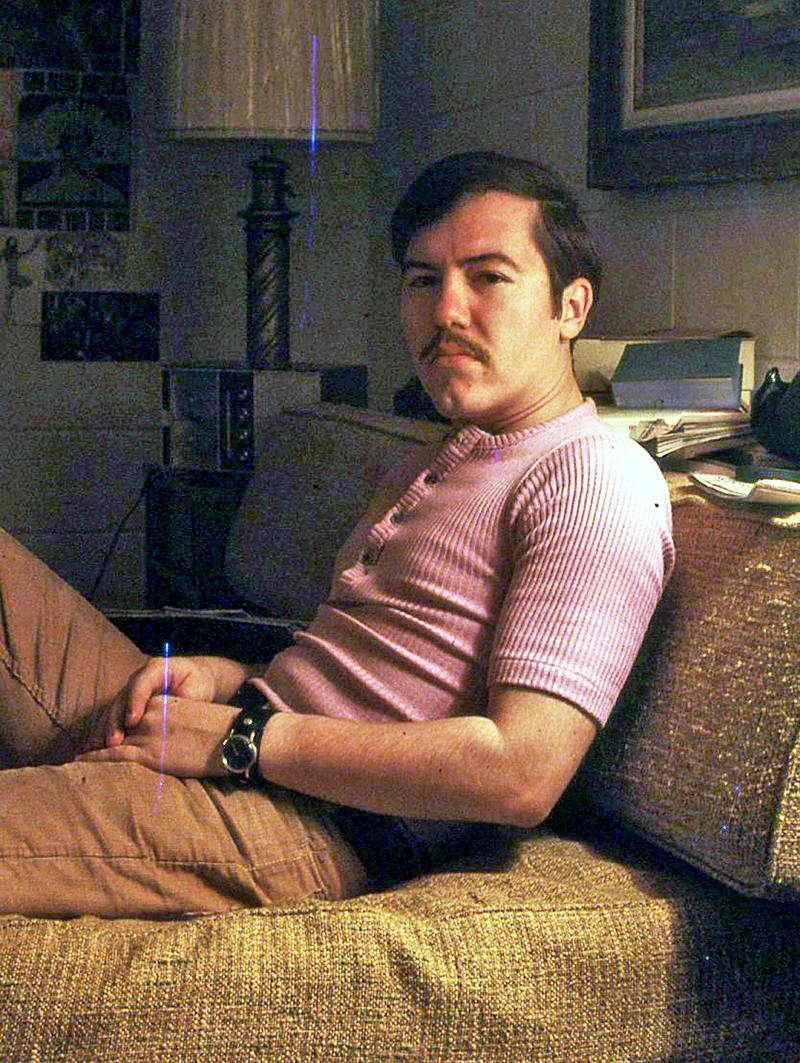

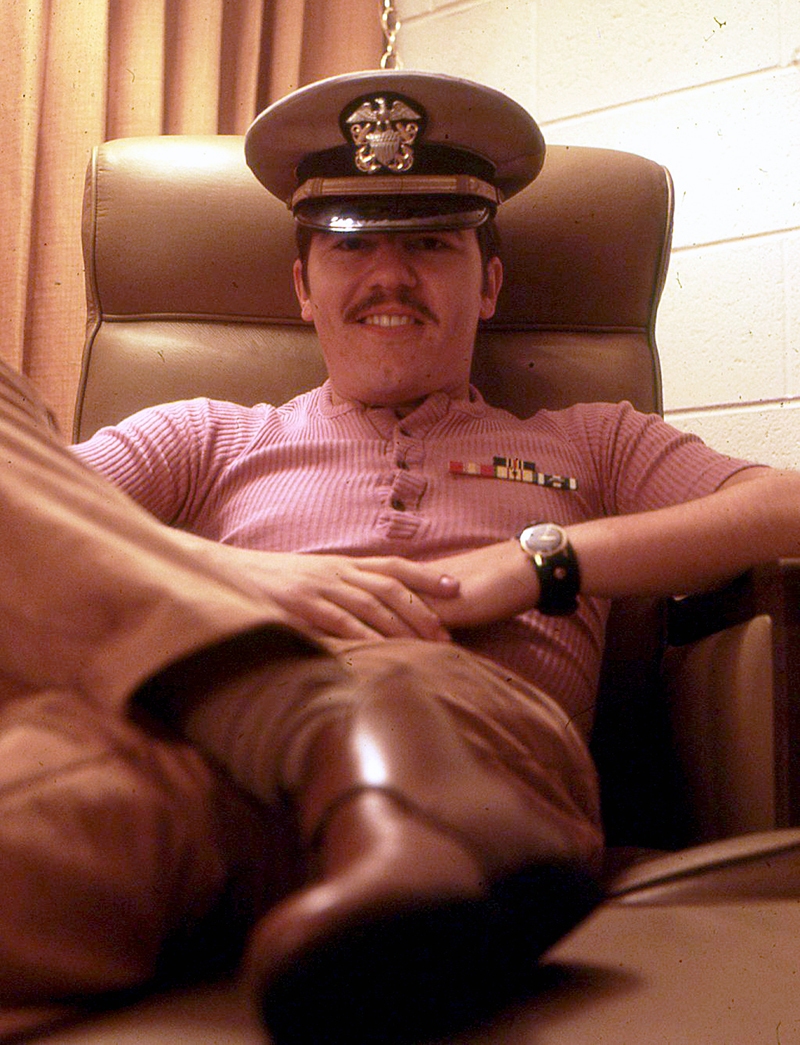

Sometime earlier, I had tried my hand at taking “selfies.” Not at all as easy to do then as it is now, I placed my SLR on a tripod and set a timer. You couldn’t just look to see the results. You had to send the film out to be processed so it was several days before you could review what was captured. I always used slide film at the time.

Below is a collection of such old-fashioned selfies. Some give a glimpse of the civilian I was soon to become. (Click on the image to see larger images and then arrows to see others.)

.